Photographs

Built on an escarpment, Dir'iyah overlooks the date groves and fruit trees of Wadi Hanifah. The surrounding land was originally owned by Ibn Dir, who gave his name to the whole oasis settlement.

Dir'iyah was first settled in 1446, but its importance derives from its being the capital of the first Saudi state from mid 18th century until 1818. Here in 1744 is where the alliance was struck between the city's Sheik Muhammad ibn Saud and Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahhab, the religious reformer.

This agreement started a struggle which was to last nearly 180 years, into the beginning of the 20th century, until the Hijaz and Najd territories were united finally by Ibn Saud.

The House of Saud had undertaken to support the Wahhabi movement, even to the extent of jihad (Holy war), which was to occur often because of strong opposition to the new doctrine from across Arabia, from Riyadh to Mecca and Medina.

So alarmed were the Ottoman authorities in what used to be Mesopotamia (now southern Iraq), that Ibrahim Pasha, the son of the governor in Egypt, laid seige to Dir'iyah in 1818 for six months, eventually razing the city to the ground. Consequently most of the mud buildings are in ruins following bombardment by the Turkish-backed Egyptian army. Houses were totally destroyed and every tree in the palm groves was cut down.

You can look down from the heights of the old ramparts into the wadi through which the Egyptians dragged their heavy artillery to the citadel of Turayf, where the Saud family made their last stand.

“Although the Egyptians were estimated to have lost 10,000 men, the defending Saudi forces lost only 1,800.”

Across the other side of the wadi, as in other places around Dir'iyah, stand watch-towers which guarded the approaches.

Near the centre of the city is the Grand Mosque, which is being reconstructed using original building techniques. Mud bricks can be seen laid out on the ground to dry and set hard.

The buildings were constructed with loopholes rather than windows, more for ventilation than to let in light.

And door heads were constructed like this, presumably where load-bearing lintols were not available.

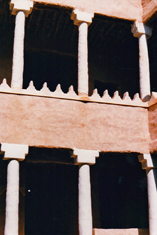

Palm trunks were used as supports inside the buildings, particularly for the arcades around inner courtyards, as here in the Grand Mosque.

Roofs were of mud spread onto a lattice of palm branches, supported by palm trunks. Rainwater was discharged by chutes made from hollowed-out palm trunks let into parapet walls.

Doors with painted decoration, studs and other ornamental designs were the only splash of enrichment in the midst of otherwise great sobriety.